At King County’s northern edge, a block east of Highway 99 between a Costco and a Home Depot, red buses and blue buses march through the Aurora Village Transit Center, each exhaling five to 10 people before a separate coach inhales them again and turns south.

It’s 8 a.m. on a Wednesday, among the busier days for travel and office work in a county still adapting to the fallout from the pandemic. The people who make up the steady churn are a mix of races and ages, many whose first language is not English, many who don’t have cars at home, and most on their way to work: a machinist, a student researcher, a music teacher.

In the months after King County shut down for COVID-19, this stop dropped to 16% of its pre-pandemic use. Where an average of 17 people boarded each King County Metro bus here in 2019, just three did in 2020, according to data provided by the transit agency.

Riders returned to the stop in 2022, most taking the popular RapidRide E Line to and from Seattle. Through the first quarter of this year, the rebound is near complete: The number of people using the Shoreline-based transit hub is 95% of what it was in 2019.

The Seattle Times analyzed this and more than 7,000 King County Metro stops, measuring ridership against its pre-pandemic self. What emerges is a picture of the geography of transit use as it’s evolved through the pandemic years, where some people, almost unwaveringly, continue to rely on bus service and where others have returned slowly or not at all.

“We all saw choice riders fall off and lifetime riders hang on,” said Ryan Mello, a member of the Puget Sound Regional Council and Pierce County Council. “Those who were always relying on transit remain so.”

Almost every stop in the system saw dramatic declines as lockdowns took hold, the analysis shows, but in the more middle- and low-income parts of the county, with a higher population of people of color, ridership dipped less and returned faster. In wealthier, whiter pockets, ridership plunged deeper and is further from what it once was.

Some stops have opened or closed, and foot traffic at others has morphed with shifts in service, the addition of three new light-rail stops, a new RapidRide line in West Seattle and other changes. Stops near schools saw major swings as in-person classes returned.

The changes give urgency to Metro’s long-term plan to provide more frequent and reliable all-day and weekend service, nudging away from being a system built around commuters.

“The trends of where people have continued riding makes the case even more clear for some of the things that we might have been thinking about or hearing about from the community before,” said Katie Chalmers, managing director of service development with Metro.

In Ballard, stop 28210 on Eighth Avenue Northwest and Northwest Market Street was among that neighborhood’s busiest; the No. 28 picked up more than 30 people from this stop per trip in 2019. That plummeted to fewer than three in 2020. Ridership has increased recently — the 28 serves commuting Amazon employees who now must go to the office at least three days a week — but earlier this year still sat at 42% of its pre-pandemic passenger flow.

Metro’s own evaluations have long shown that lower-income households, people with disabilities and people of color use the bus system at higher rates. The pandemic distilled ridership down to those who rely on it most, hastening plans for a service that better suits those who use it all times, for all reasons.

“The best way, and the only way that we can meet that effectively is just frequency,” Chalmers said.

Reliable riders

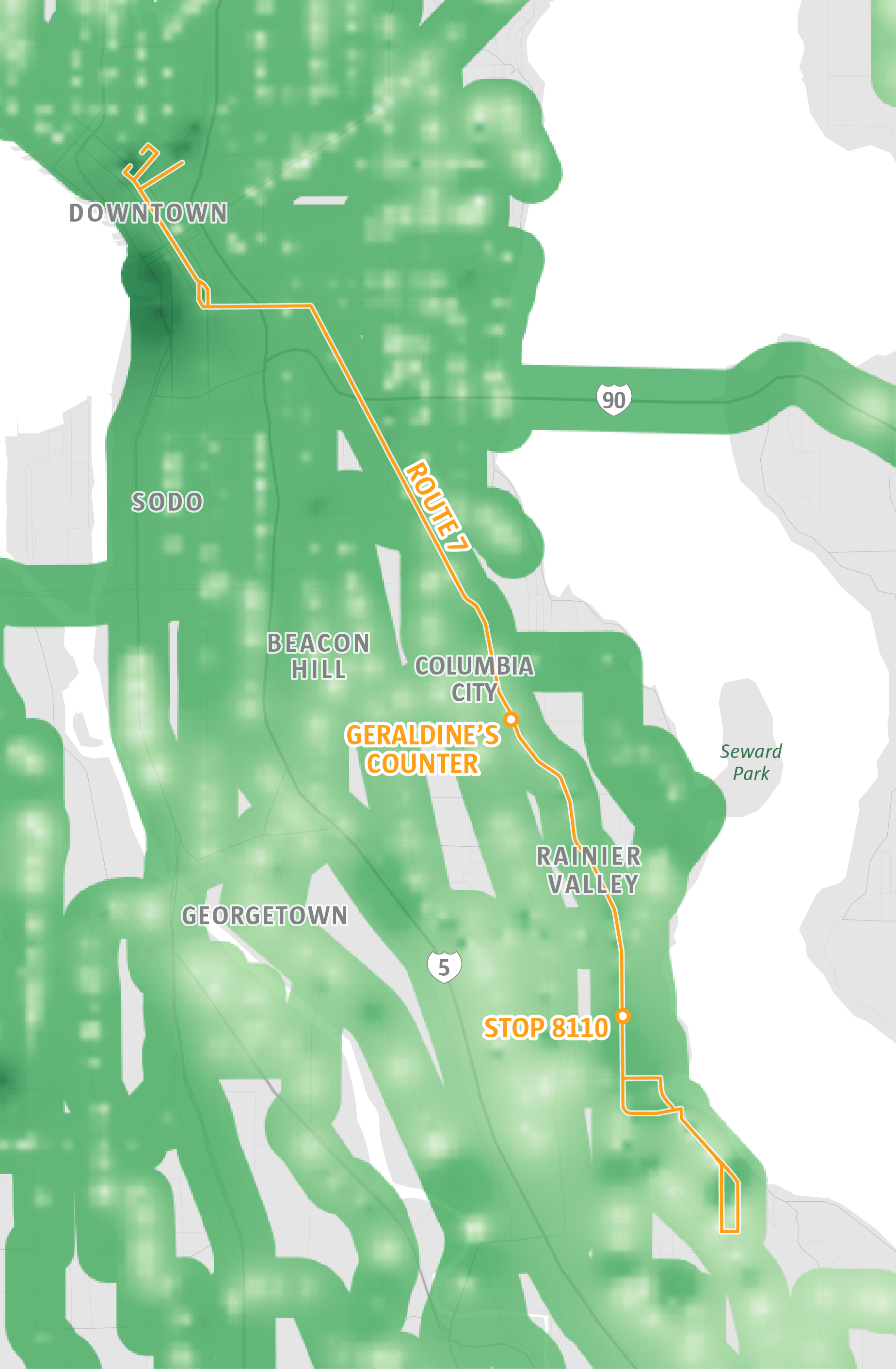

Mike Stegmann never stopped riding the No. 7, his bus for many years now. On a recent Tuesday, just past 9 a.m., he waited at stop 8110 near Rainier Beach High School for a ride to Geraldine’s Counter for breakfast in Columbia City.

Stegmann doesn’t own a car, so even with the arrival of a strange new virus in 2020 he kept taking his almost daily rides to shop, go downtown, run errands and pick up the dogs he walks for work. He took precautions but didn’t see much alternative.

“There’s always going to be a reason not to ride the bus,” he said, “but it’s a long walk, alternatively.”

Stop 8110 is one of very few in the system that saw almost no decrease in ridership, sliding to 95% in 2020 and hovering there until 2023. Now, ridership is 120% of what it was in 2019. The 7 and the 9 buses shuttle people up and down Rainier Avenue, one of the city’s busiest arterials.

Few other stops showed the resilience of 8110, but the surrounding neighborhood is indicative of where ridership remained strongest: 30% of the census tract is at or below 200% of the poverty level and for 20% of the people who live there, English is not their first language, according to data from the U.S. census.

The county’s own data confirms it’s these neighborhoods that retained the most riders, a trend not unique to King County. Residents are less likely to own a car or to hold a job that allows for remote work.

The correlation between transit use, race and income status means that transit agencies’ equity goals align closely with their mission of gaining back ridership, said Jarrett Walker, a well-known public transit planning and policy consultant. Just because ridership is stronger in some parts of the county doesn’t mean there isn’t still room to grow.

“Pursuing lower-income riders, and treating them not as dependent but potential customers, has really been the key to a lot of the recovery and will continue to be the key to a lot of the growth,” Walker said.

Doing that could mean a de-emphasis on rush-hour service, a change Metro was hoping to make even before the pandemic. The agency excelled at commuter service pre-pandemic. But while peak rides will remain an important part of what the agency provides, there are already signs of a shift: In Seattle in 2022, the morning and evening weekday rush made up only 50% of ridership, down from 60% in 2019.

Looking out to 2050, Metro has a lofty goal of spending $28 billion — not currently budgeted — to increase service by 70%, intertwining the bus system with new light-rail lines to West Seattle, Ballard, Everett, Redmond, Issaquah and Tacoma.

Degraded service

For many riders, Metro service is worse than it was before the pandemic. Route cancellations and no-show buses have become commonplace, and on-time performance is worse than it’s been since 2019. The agency has acknowledged these issues, pointing to increased traffic, supply chain issues and staffing shortages and planning cutbacks to make the schedule more predictable.

Trips to work or the store or to see family that take 20 minutes in a car take an hour on the bus, said a woman from Guadalajara, Mexico, who didn’t want her full name used because she doesn’t have a current work visa. With each missed connection, the trip slows.

“It’s the worst thing, here, after loneliness,” she said.

Winning back the riders who still haven’t returned means improving that reliability at all times, said Chalmers.

“Transit has to be attractive; it has to be reliable for people to want to use it,” Chalmers said. “We need to be there when the schedule says we’re going to be there. And that’s something where we’re working on improving, but we haven’t been at where we want to be in terms of delivery for the past couple of years.”

In Ballard, Matthew Webb, an Amazon employee, said his bus is sometimes standing room only. On a Tuesday morning around 8:30, about 15 people wait for the 28 to arrive; when it does, it’s crowded.

But as morning shifts to midday, the stop quiets.

“After peak hours it feels like the bus just doesn’t happen,” Webb said.

The opinions expressed in reader comments are those of the author only and do not reflect the opinions of The Seattle Times.